Witches are real, and they’re on TikTok

NOTE: This post was originally published on the Pulsar Platform blog in May 2022 but it doesn’t exist there anymore, and it is one of my favourite social listening analysis pieces. I was responsible for all the research that went into the piece, but it was actually written by Alex Bryson and Dahye Lee.

Once upon a time, calling yourself a witch would see you cast out of society, or worse. Today, describing yourself as such places you within a cultural movement whose influence on media, lifestyle and now corporate storytelling keeps on growing.

Witches have long featured in entertainment, with a procession of Glindas, Sabrinas and Hermiones helping rehabilitate their reputation within the mainstream. Against this ever-growing presence within both traditional and modern media spaces, however, we’ve also seen the continued growth of witchy, wiccan or pagan practices and aesthetics as a lifestyle choice – and a corresponding decline in the use of witch as a political or public slur.

Why has this happened? Certainly it’s helped that Hilary Clinton, the popular target of many ‘witch’ slights, has exited the political stage. But we’ve since seen the slur applied to a range of different political subjects, from the rise of Marine Le Pen, to the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe vs Wade.

And so, while the term’s use in the political theatre has dipped, the shift in emphasis is as much due to the explosion of interest in witches elsewhere. Because not only have practitioners remained a constant within written fiction, and continued to feature more and more within streaming and gaming, witches have also, in 2022, been mentioned well over double as many times in conjunction with lifestyle words and phrases as they were in early 2018.

This trend is typified by #witchtok, which has ushered in a new breed of ‘baby witch’.

As with many trends that begin on TikTok, the trend has quickly cycled from niche interest to mainstream concern to the kind of in-joke and vocabulary intrinsic to the platform. It’s also attracted a fair degree of opprobrium, with experienced practitioners often resistant to a trend that can sometimes prioritize the aesthetic over the spiritual, or else run roughshod over existing practice.

So how do these values and behaviours differ within the wider witch subculture? Who are the audiences engaging with the topic? And what do we mean when we say ‘witch’?

By using Pulsar TRAC to analyze over 800k posts made across Twitter, Reddit, Pinterest, Tiktok, blogs, forums and more, all posted within the USA, UK and Canada between February and May 2022, we look to unearth insights that will answer these questions.

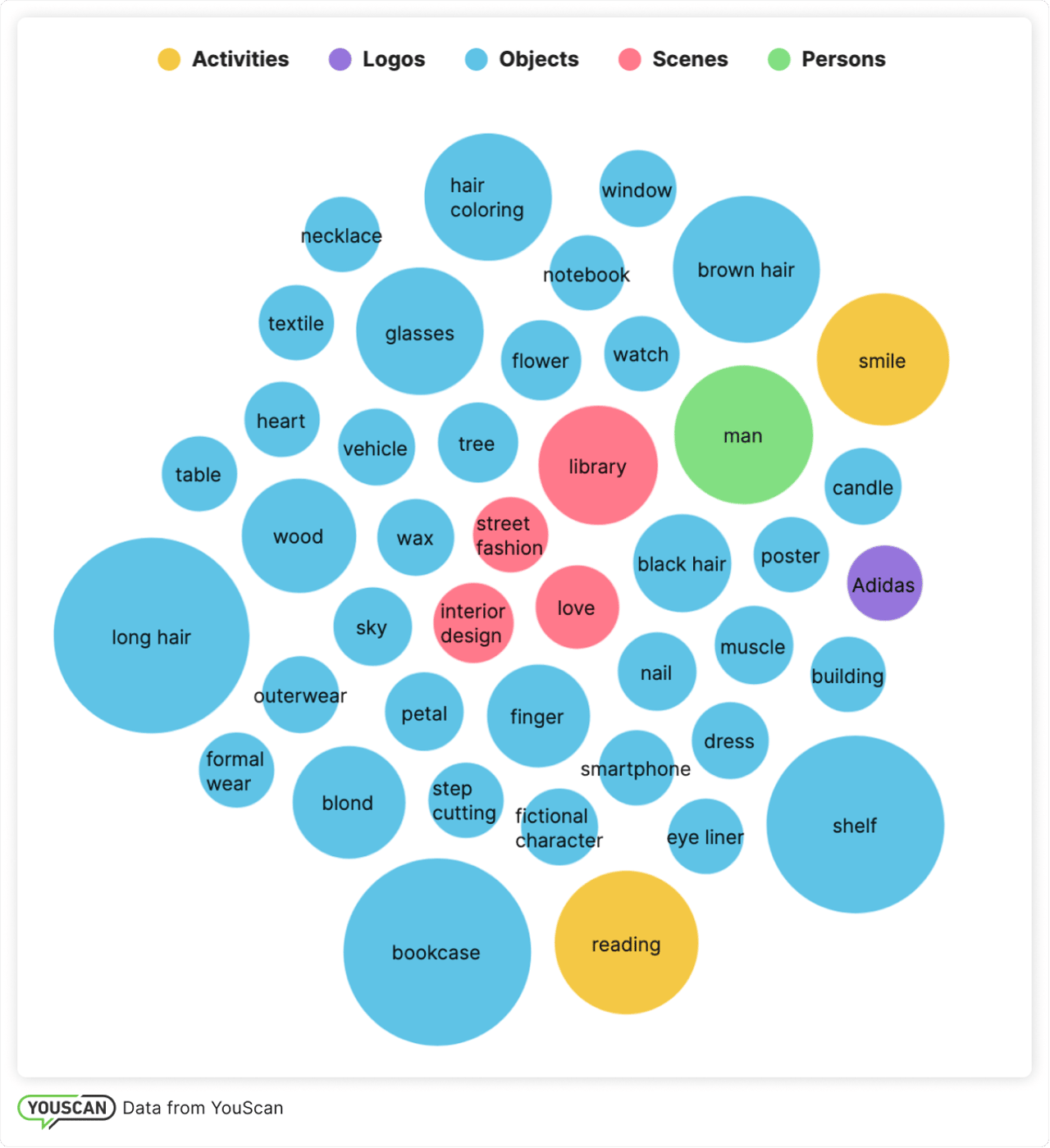

First of all, what is it that witches actually do?

We see the trend incorporate and intersect with astrology and herbal medicine:

And, of course, there’s no shortage of spells. As follows from witch tradition, these incorporate a number of physical objects, ranging from ingredients like bay leaves to magic-specific equipment such as spell jars.

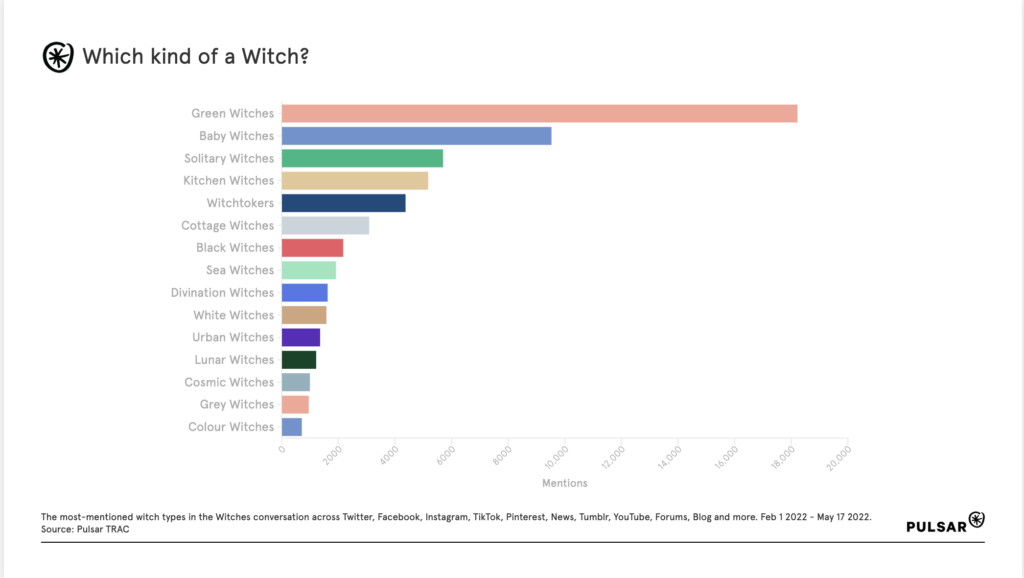

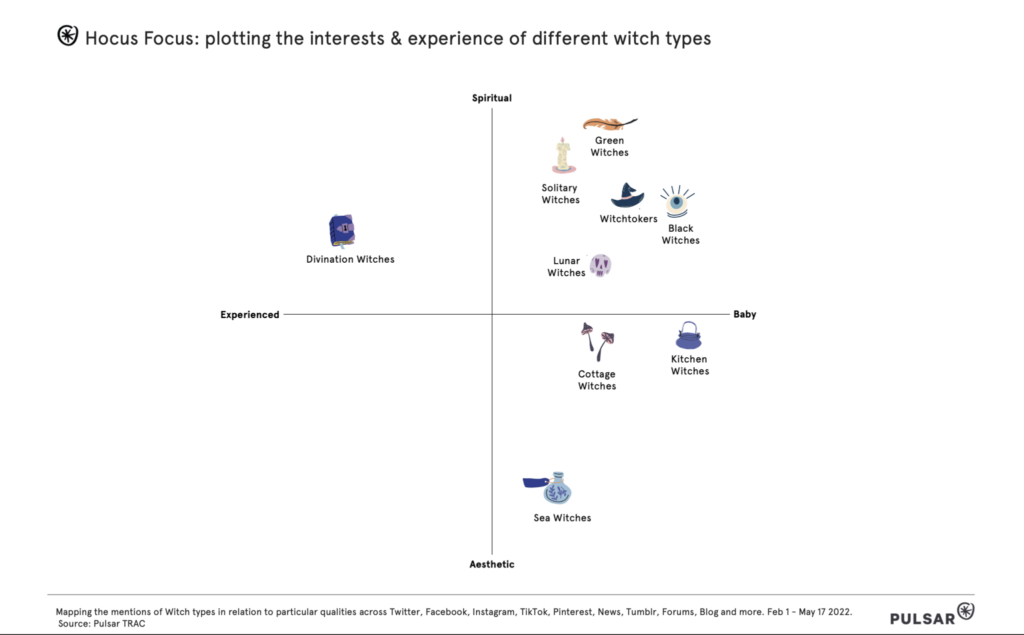

The behavior, aesthetic and experience level of these witches differs from community to community.

So Green Witches, for instance, base their practice in natural elements like plants, animals and stones. Kitchen witches, on the other hand, practice magic through cooking, and the properties of individual ingredients. These terms aren’t exclusive either. An urban witch can both live in the city and also practice the unethical practices of a black witch.

By mapping the relative experience of these witches and whether the language around them leans more towards the spiritual or the aesthetic, it’s clear that new adopters, or ‘baby’ witches, have become more prominent within the space.

There’s another factor at hand, though, which is that young witches are more likely to classify themselves in this way. Older witches are more polymorphic in their custom, likely to engage in many of the customs featured above, but less likely to define themselves as belonging to one particular subset.

If you want to talk to this subculture, it’s important to understand that they will want to be addressed and understood in very different ways.

So who is it who compiles this subculture in the first place?

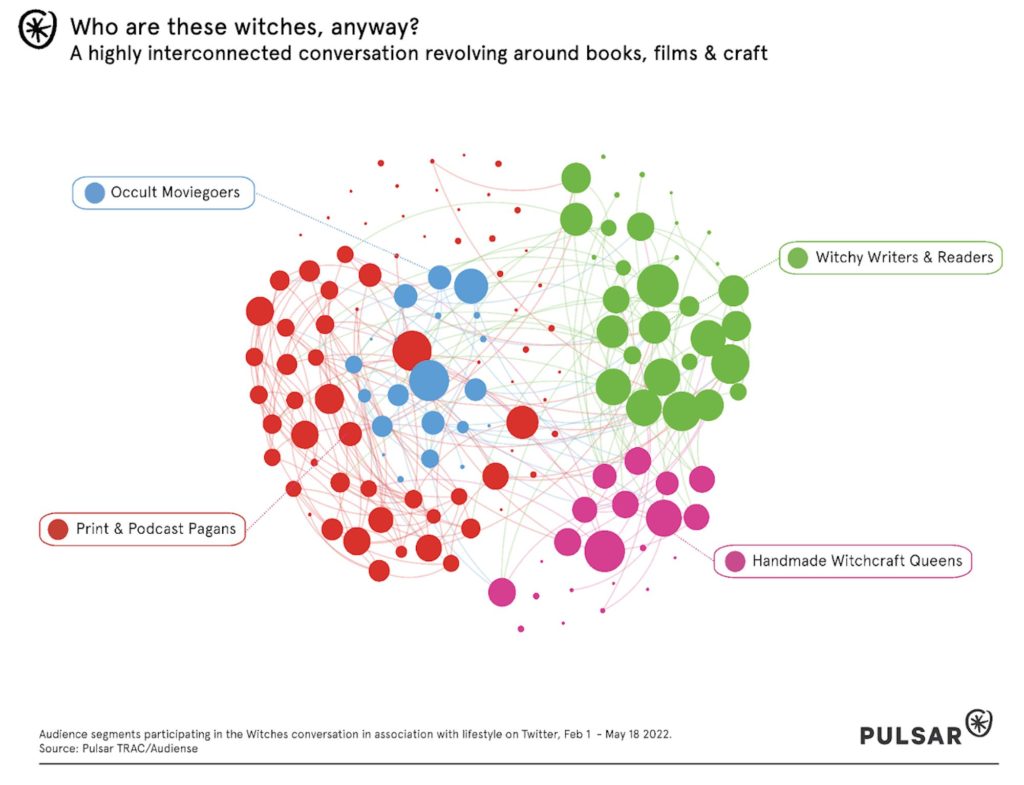

When we isolate the communities engaging in the conversation on socials, we still see a very pronounced affinity for books, movies and podcasts. It would appear that witchcraft as a lifestyle trend is not evolving parallel to the witches within media conversation, but rather incorporating many of the same members.

Print & Podcast pagans share a common affinity for publications, publishing houses and podcast channels that specifically explore witchcraft in relation to personal growth, such as the WIld Hunt or Llewellyn.

Handmade Witchcraft Queens, on the other hand, primarily follow accounts that create and sell household or fashion items, from crochet to glassware to jewelry.

As such, the wider community appears to largely cohere around these two primary activities: media consumption and small scale goods creation and consumption. If there’s a singular point of difference between these two behaviors, however, it’s that the subculture are at least used to external corporate bodies creating the media they consume (for all that it invariably creates a certain amount of blowback).

Conversely, the importance and intransience of physical objects within the culture’s belief structures mean independent retailers remain dominant, and are unlikely to be usurped – something we’ll explore in more detail shortly.

Of course, being a witch is not simply a matter of engaging with wiccan practices or dressing in a certain way. There is also a significant overlap between elements of the subculture and social causes.

To some extent this takes the form of as people self-identifying as witches look to drive change using a culture distinct from the patriarchal norm. And here, it’s important to distinguish the ‘religious’ aspect as something distinctly political for being female-led and formed.

At the same time, however, we also see a lot of attention directed towards the self, with Witchtok in particular featuring a number of affirming and even anxiety-tackling spells:

It goes without saying that these social aspects are engaged in very different ways. And, using Pulsar’s Communities integration we can see how these audience segments display different attitudes.

LGBTQ activism, for instance, is a powerful motivating factor for Witchy Readers and Writers, whereas the Handmade Witchcraft Queens spread their own advocacy more evenly between feminism, supporting the culture’s religious aspects, and LGBTQ rights.

So, witches are a subculture entirely fixed on the political and the unearthly, right? Not quite.

We’ve already seen pronounced behaviours around buying and selling and, if #witchtok has emphasized anything, it’s the tension between different forms of consumerism within the space.

Once, spiritual shops were the only way of accessing the equipment and supplies one needed to be a witch. Online platforms subsequently made all sorts of horizontal economies possible within the space – something that can be evidenced by how many accounts within the space either describe themselves as creators, or else cluster around craft as a topic.

In addition to providing links to, and information about, particular items like Spell Jars and Terrariums, there’s also a vibrant thread of conversation that focuses on budget witch tips. This thread connects many of the ‘baby’ witches new to the scene with some of its more established faces – after all, witches aren’t immune to wanting to save money.

The witch subculture is not a closed shop either, with numerous overlapping trends sharing common features such as astronomy, nature, spells and female empowerment – as well as that same sense of horizontal, community-driven economy.